What does it mean for a place to be "walkable"?

Put simply, it's the freedom to walk.

A walkable place is one where you feel encouraged to walk; one where it is enjoyable to walk; one where it is safe to walk and where it is comfortable to walk; one where you can walk. It's a place where you don't need to drive 20 minutes for every errand you must run.

If this sounds appealing, you're not alone. There is substantial demand for more walkable places. In fact, a study by the Urban Land Institute (ULI, 2015) found that around 50% of people say walkability is a top or high priority when considering where to live. Similarly, 52% of all Americans, and 63% of millennials would like to live in a place where they do not need to use a car very often. There is something about the freedom to walk that just feels so human. It was, of course, the "original" transportation mode for our species.

|

| Photo by Miquel Fabré on Foter |

The thing I love about walkability is that is is by no means restricted to urban areas in the way that, say, public transit is. In fact, some of the most walkable places I've visited are in decidedly non-urban areas. Take London, Ohio, for example. Featuring a population of a whopping 10,000 residents, London is actually quite walkable. It's downtown area is filled with shops, restaurants, bakeries, all in the same place, boasting wide sidewalks, lush treescape, and solid pedestrian infrastructure. This quaint little town is a very pleasant place to walk, but it is not "urban" by any stretch of the imagination. Small towns are often the epitome of walkability.

It is clear that many Americans long for this sort of lifestyle. So, then, what can we do to make places more walkable? First, let's look at the Theory of Walkability.

First: Jeff Speck's "Theory of Walkability"

Jeff Speck is really an urban planning superstar. You'd be hard pressed to find someone with a more impressive resume: he was Director of Design at the National Endowment for the Arts, let the

Mayor's Institute on City Design, and now owns his own firm, which has completed countless projects to enhance in cities and towns. Speck has written numerous critically acclaimed books on urban planning, and is a fellow of the American Institute of Certified Planners and the Congress for New Urbanism. It's safe to say Speck knows his stuff.

But where Speck (2012) is most influential is in walkability, his study of which he calls his "project for a lifetime". In his groundbreaking book,

Walkable City (which has become one of the

most popular urban planning books ever)

, he lays out what he calls his "General Theory of Walkability".

"To be favored", he argues, "a walk has to satisfy four main conditions: it must be useful, safe, comfortable, and interesting" (Speck, 2012).

When you think about it, Speck hits it spot on. You are not going to walk anywhere unless it actually makes sense to (especially in car-centric America). If cars whizzing by as you stroll along the narrow sidewalk makes you fear for your life, you aren't going to walk. If you feel uncomfortable because of extreme heat and lack of shade, you aren't going to walk. And finally, who wants to walk in an ugly, boring area?

It is clear that these criteria are crucial in making our cities (and towns, villages, whatever) more walkable. But how can we do it? To solidify the ideas, I will draw on my own experiences navigating on foot through Columbus (it is, after all, the only "big city" I've actually lived in) supplemented by some of Speck's wisdom.

The Importance of Land Use

I would venture to say that most people consider the University District to be a walkable community. I certainly think so. If I need something from Target, it is just a 10 minute walk away. Meeting a friend for dinner? Just 10 minutes away. Going to class? Just 10 minutes away. Grabbing a beer with friends? 2 minutes away (I know, right?). Pretty much everything I could possibly need is within a 15 minute walk.

Being an area with a very high student population, it makes sense that this area is walkable. It just doesn't make sense not to walk to places. Parking on campus is very expensive (as it should be; otherwise we would have cars everywhere, and the charm of our campus would be completely ruined), and the one-way streets and discombobulated street pattern means it would take longer to drive in some cases than to just walk.

Why is this the case? We have a dense land-use pattern here that is very conducive to walking. Think of High Street, for example. There are apartments, restaurants, doctor's offices, bars, stores, and anything else you might need, all in the same place. When land-use is mixed, you naturally get people walking. I think part of what makes college so interesting for people is that they get exposed to this lifestyle they've never gotten to experience before.

|

| The mix of land uses at near Hauptwache, Frankfurt am Main, Germany create an environment highly conducive to walking. Photo credits: me |

The US is notorious in having segregated land uses. When your house and grocery store are 5 miles away, of course you have to use a car. This is why mixed land-uses is essential for creating walkability. I saw a tweet once that puts this in perspective (from Phil Ritz): segregated land-uses is like a holiday dinner where you have "salads on one table, drinks on another, sides on a third table, and the main dish in the living room. Then watch the chaos as everyone tries to eat. [Our separated land use] create(s) traffic out of thin air" (

Ritz, 2021). Beat the traffic by getting the land-use right, and put everything in the kitchen where it belongs!

Infrastructure Matters: Give Pedestrians Their Space!

Speed kills. Literally. In fact, pedestrians struck at 31 mph are 25 percentage points more likely to be seriously injured in a collision than those struct at 23 mph; just an 8 mph difference (Tefft, 2011).

So how can we keep pedestrians safe? Slow the cars down.

"Traffic calming" is the idea of doing just that: using built infrastructure to convince motorists to be a little more cautions before deciding to put the pedal to the metal.

I know, we all hate speed bumps. I don't really care for them too much, either. But I'm happy to tell you that there are a plethora of options to slow traffic down without ruining your suspension.

Intersections

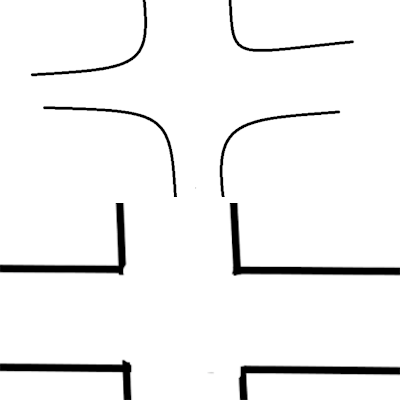

Let's talk for a second about intersections. Boring, I know. But consider the figure below. I am not a graphic designer, so bear with me.

Wow. That is not pretty. Like I said, not a graphic designer, but you get the idea.

The top intersection features long, curved turns, while the bottom features shorter, sharper ones. The curved nature of the top intersection encourages motorists to pass through the intersection at a high speed. There is nothing standing in their way when they try and make a right turn. Well, except the pedestrian, but since the motorist was driving through this pedestrian-unfriendly intersection, lured on by the gradual, smooth curve, they were encouraged to not even think about the possibility of a pedestrian trying to cross. By the time they realize, it's too late.

Contrast this with the bottom intersection, which is much more "boxy". It is much more difficult for a motorist to pass through this intersection at a high speed, and since the turn is sharper, they navigate it much more slowly. They are more aware of their surroundings (they don't want to run over the curb), and as a result, they are mindful of the pedestrian trying to cross the road. We can sacrifice 1.5 seconds of the motorists time to ensure the situation does not end in tragedy, can't we? Patience is a virtue, as they say.

Wide Streets

Speck argues that many of the streets in the US are simply too wide. In fact, he notices that there is this idea amongst traffic engineers that increasing the width of traffic lanes improves safety. This has resulted in many cities building lanes on roads that are 13+ feet wide each, when the typical car is just 6 feet wide (Speck, 2012).

When you give the motorist this unnecessary space, they are going to feel compelled do drive faster. More space means more freedom to step on the gas. As Speck puts it, "highways have twelve-foot lanes, and we are comfortable negotiating them at seventy miles per hour, wouldn't we feel the same way on a city street of the same dimension?". As is noted by Ewing and Dumbaugh (

2009),

"In dense urban areas, less-“forgiving” design treatments—such as narrow lanes, traffic-calming measures, and street trees close to the roadway—appear to enhance a roadway's safety performance when compared to more conventional roadway designs. The reason for this apparent anomaly may be that less-forgiving designs provide drivers with clear information on safe and appropriate operating speeds."

Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg quipped "some roads need to go on a diet" (

Yen, 2021).

Road diets are gaining traction in communities all around (and indeed are very common in the planning world), owing to the growing notion that our roads are too fat. So let's put them on a diet. Let's narrow our road lanes and give pedestrians and motorists alike what they need to stay safe. Next time you're on a road with cars parked on the street, notice how much room there is between its left side and the lane-line. Do we really need all of that space?

One Way Streets

I am completely astounded by how many one way streets there are in major cities in Ohio. One way streets are terrible for walkability. Why? They give the perception of a fast lane. They invite people to (perhaps even unconsciously) drive faster. One way streets scream "hey, come drive really fast here, without any regard for pedestrian safety". There is just something about the lack of traffic approaching from the other direction that lures motorists on. Think about it this way: Imagine driving on I-71 but where the north and southbound lanes were not separated. Would you feel as comfortable driving 70 mph? I certainly wouldn't.

Also, if you don't buy this, one-way streets are terrible for local businesses too, not just walkability. Consider a business on a one-way street. Since traffic only travels in only one direction along their street, they lose half of the traffic because when motorists return home, they have to travel along the other part of the "one way pair"- the part where their business is not located. Speck (2012) notes that such roads "distribute vitality unevenly".

Physical Separation

I've been waiting 22 years (my whole life) to use the phrase "devil's strip" in a relevant context. If you don't know what a devil's strip is, it's

Akron vernacular for the grassy patch between the sidewalk and the road. You know, that thing that the government controls but you are responsible for mowing.

In any case, devil's strips (tree lawns, or whatever) can greatly enhance pedestrian safety and comfort by adding a degree of separation between the roads and the pedestrian. Better yet, trees can be planted in the devil's strip to provide physical separation as well as a physical barrier to protect the pedestrian from fast moving traffic.

The photo below showcases High Street here in Columbus. Notice how there is a large amount of space between the sidewalk and the road, and how this area is lined with trees. This is a dream for the pedestrian, who can feel very safe from cars as they go on a "High Street stroll", as OSU students like to say. On street parking can accomplish a similar thing, as the parked cars provide yet another barrier between pedestrians and fast-moving traffic, as well as an incentive for motorists to slow down.

I know, where the heck are we going to get all of this space to build my tree-lined devil's strip? Just narrow the streets. Duh. They're already too wide.

|

| High Street- a highly walkable environment where the devil's strip and trees provide physical separation and protection to the pedestrian, enhancing comfort. Photo credits: me |

Pedestrians in car land, or cars in pedestrian land?

Walkability can stem from changing the way we fundamentally think about crossing the road.

The way crosswalks work in much of the US puts the needs of cars over the needs of pedestrians. To cross the road, a pedestrian first must wait for their turn to cross, as dictated by whenever the traffic lights are red for cars. Once it becomes their turn, they must descend a small ramp to get to street level, and once there, the illusion is that they are temporary visitors in the house of the automobile. They are simply allowed to exist there, but it's clear the space is not their own. Cars are given priority in pedestrian spaces. I can't tell you how many times I've tried to cross a road where a car is sitting in the crosswalk. In America, a pedestrian is living in car land.

As a

new urbanist, I always support designing places with

people as the top priority, not cars, because cars are not people. What if we designed pedestrian crossings that prioritize

people, and not cars?

The Netherlands is known for a lot of things (although you might be surprised to learn that recreational marijuana is actually de jure illegal in Amsterdam, but de facto it isn't, obviously). Prime amongst them are flood control, their incredible English speaking abilities, and being super pedestrian and bike friendly. In Amsterdam in particular, crosswalks are designed for pedestrians. The attitude is that the car is a temporary visitor in the world of pedestrians.

How do they do it? Instead of making pedestrians descend to street level to become a temporary visitor in car world, they extend their sidewalks across the street. That is, the pedestrian stays at the same level as the sidewalk the entire time. This creates a "raised crosswalk". If a car wishes to pass through pedestrian land, they must slow down (the infrastructure makes them do this) and let the pedestrian cross before proceeding. People are allowed to cross at any time, not just when the lights are red for cars. Autos are seen to exist in the land of people and pedestrians, not the other way around like in the US.

It's actually kind of funny how backwards this seems in the American psyche.. In America, pedestrians are expected to look both ways before crossing the street, allowing cars to pass before they do so. But in the Netherlands, motorists are expected to look both ways before crossing the crosswalk, allowing pedestrians to pass before they do so. Changing the mindset into one that is focused on humans will do wonders for walkability in the US.

For more about how the Dutch do it, check out this video from the YouTube channel Not Just Bikes.  |

| A raised crosswalk like the ones common in Amsterdam. Photo by Dylan Passmore on Foter |

Traffic Signaling

At the intersection of 16th and High, there is a Target. Everyday when I walked to class, I used to cross High Street here. There used to be what we call a "flashing beacon". You're familiar with them- It's the thing where you push the button and these lights start flashing overhead, alerting motorists to yield to pedestrians. Yet for reasons that I will never understand, they removed this signal, and now it is simply a marked crosswalk. Now, I avoid that intersection because motorists, for one reason or another, seem to think they don't have to yield any more.

There is a world of traffic signals out there that have proven effects on pedestrian safety. For example, a literature review from Monsere and Figliozzi (2016) finds general consensus that these overhead flashing beacons increased yielding rates when installed. Also, the authors found consensus that the installation of another signaling device, called rectangular rapid flashing beacons (

RRFBs), have led to a statistically significant reduction in pedestrian-vehicle conflicts. Even something as simple as putting "pedestrian crossing" in paint on the road has been shown to have safety benefits for pedestrians (Monsere and Figliozzi, 2016). This only scratches the surface of the potential impacts of better pedestrian signaling at crossings. See more

here.

|

| Photo by marfis75 on Foter |

I couldn't tell you why the City of Columbus removed the flashing beacons from that intersection. I've heard numerous anecdotal stories from friends longing for its resurgence. Perhaps the City should read this article.

Let there be Light!

One of the things I hate most about our society is that women are not afforded the same freedoms as men when it comes to the ability to navigate their built environment on foot. Sexual harassment and other crimes are far too common, and it is safe to say that women often simply do not feel safe walking around at night. In fact, a study by Golan et al (2019) found that areas often considered highly walkable by conventional sources (such as

Walk Score) are often not so for women. They constructed their own walkability score for women, and found that it does not correlate well with things like Walk Score.

This leads me into my absolute favorite academic article I've ever read. I know, how nerdy, but this study is really remarkable.

Researchers at the University of Chicago conducted a study in New York City studying the impacts of street lighting on night-time crime in high-crime areas. Their experimental design is truly fascinating: they randomly assigned lighting dosage to New York City Housing Authority complexes by essentially randomly placing 319 temporary light towers across 40 housing developments, meaning there was random variation in treatment assignment (or, essentially, "brightness") such that each neighborhood had a different number of light towers per square blocks of area. Random assignment is the statistician's/econometrician's dream- it is essential to establishing causation.

The researchers found that increasing the dosage (that is, light towers per block) reduced crime by 4%. I know, it doesn't seem large, but as the researchers point out, this is the same percentage we would expect to see from a 10% increase in police manpower. And at a cost of $80/resident, it is much much cheaper too. Keeping an inmate at Riker's Island costs $121,000, and a 10% increase in the police force would be extremely expensive (

Chalfin et al, 2021).

Clearly there are bigger societal issues here, and I'm not suggesting slapping some lights down is going to solve all of our problems. Planning is a historically male-dominated field, so much more can be done by actively including women in the planning process, giving women what they want, not just what men think they want. This idea is called

gender mainstreaming. However, increasing street lighting is a start and can have a remarkable impact, and gives us a lot of bang for our buck.

The best way to make places less shitty is allowing people to walk in their city

You like that rhyme? I think its golden.

Anyway, the single easiest way to make a city more walkable is to allow pedestrians to walk in the city. What do I mean? There are numerous examples, even in the University District and Downtown Columbus, where pedestrians are simply not allowed to cross the street at an intersection. There are others where pedestrians are banned altogether. Consider some of the images below. For some reason, pedestrians are not allowed to cross Livingston Ave at 4th Street on the west side of the intersection (but they are on the east side??) Similarly, at Summit and Lane (and Summit and 17th), pedestrians are forbidden from crossing as well.

This restriction of freedom makes absolutely no sense to me, especially when pedestrians are allowed to cross at one "side" of the intersection but not the other. These signs that you see below create an atmosphere in which pedestrians do not feel welcome. And I don't know about you, but I typically am not jumping to go places where I am not welcome. If we welcome pedestrians, they will come.

|

| Why can't we walk? Upper image is Livingston and 4th, and the bottom is Summit and 17th, both in Columbus. Photo credits: me |

Final Thoughts

People want walkable cities and places. If cities across the country want to continue to attract residents, it is clear that we need to enhance walkability. Cities that don't will be overshadowed by the ones that do.

If you want more walkable cities, I encourage you to write your politicians, attend city planning commission meetings, or advocate for change to voice your concerns and desires.

For more information about walkability, check out one of

Jeff Speck's Ted Talks on YouTube here or

here. I also highly recommend his book,

Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time, which you can find on Amazon

here.

Sources

Ewing, R., & Dumbaugh, E. (2009). The Built Environment and Traffic Safety: A Review of Empirical Evidence. Journal of Planning Literature, 23(4), 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412209335553

Monsere, C. and Figliozzi, M. (2016). Safety Effectiveness of Pedestrian Crossing Enhancements. SPR 778. Portland, OR: Transportation Research and Education Center (TREC).

https://doi.org/10.15760/trec.168

Speck, J. (2012). Walkable city: how downtown can save America, one step at a time (1st ed). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

This is so interesting. My husband and I have been listening to zoom meetings with Cuyahoga Falls and Akron about their plans for the Valley. It is like a different language and I may contact you for a tranlation. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteThank you! Yes, I've read a bit about that plan too. Walkability can enhance our lives to an extent that many people just don't realize, and it's because their neighborhoods and cities have been built for cars, not for people. Which is completely understandable, since it's hard to see what's possible when we are so used to things being a certain way. I'm glad you found the article helpful, and hopefully you are interested in more person-centered development patterns! Maybe I should write an article about the Merriman Valley plan...

Delete